Against (ethnographic) Interpretation

By Anjana Bala

I first stumbled upon Hemen Majumdar’s painting in a book in the Madras Literary Society, a colonial library built in 1817 now housing rain- soaked books and a dated pulley system. The painting immediately struck me as odd with its Renaissance stylization as the subject of the painting was an ornamented Indian woman. The image was striking, and I found myself never quite arriving at the work, moving between appreciating its aesthetics, the precision of form, a supposed narrative, and then what some would call the irreducible dimension of the work. This piece, which was indicative of a trend in Majumdar’s erotic works, was an oil painting of a woman dressed in a dripping wet transparent sari at the edge of the river, washing something off her foot after having taken a bath in the swampy waters. The woman is far from any other person, yet her arms are adorned with bangles and jewelry. I would later learn that most of Majumbar’s paintings depicted moments of deep privacy in a mature woman’s life: during a bath, while she was getting ready, looking into a mirror, talking to herself, and the viewer is left wondering about the circumstances around her aloneness. Majumdar played with disclosure and suppression. I was most struck by how clear it was that these women weren’t just being watched, but how they were watching themselves, how they appropriated an embodied presence through their own gaze. The framing of these pictures suggest that the woman has deserted the world or has been deserted, and the viewer is left to observe an encounter with a self that has been produced by the other.

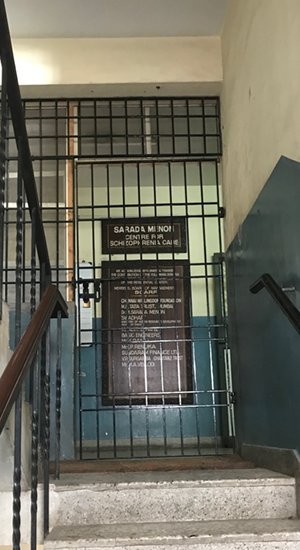

Compared to other artistic mediums, visual art has the potential to offer something immediate and frontal, where the viewer has the opportunity to confront their own gaze. Majumdar’s paintings arrived to me when I was thinking about how to frame my object of research inquiry, which was the phenomenological experiences of schizophrenia and psychosis in South India. I had spent the last 16 months researching the material conditions of psychic experiences, and part of the work included bringing the framing of schizophrenia and psychosis away from something on the “edge” of experience to something irreconcilably bound to the realities and material conditions of life. Majumbar’s painting, with its focus on the embodied gaze, reminded me of how easily my framing could perpetuate anthropology’s deeply embedded colonial gaze through curiosity, fascination, and interest. His work offered me a unique framing of dispossession, while drawing attention to anthropology’s own tendencies toward ornamentation.

Comparing a visual art work to ethnography presents a novel approach to thinking through the problematics of anthropological inquiry. Much has already been written about anthropology constructs the other, mostly through time, space, distance (between the ethnographer and their interlocutors), and the ethnographic gaze (see Fabian 1983). Equally so, much has been written about the (im)possibility of translation, variance, and difference (Clifford & Marcus 1986). In Majumdar’s painting, it is the apparent passivity of the subject of the gaze that bestows the viewer with a sense of agency. The subject of his paintings is completely alone, yet they are heavily ornamented, and viewer is left to wonder the circumstances of their aloneness. Such a suppression of detail is intentional to render the viewer with the capacity to interpret. Interpreting madness through the opacity of ethnography produces a different kind of gap (between subject and viewer). If ethnographic data has the possibility to be selected at will and manipulated to verify theories formulated in anthropological discourse, it is the passivity of the interlocutor (through distance, space, and time) the moment they are reduced to the pages of the text that facilitates such agency. In my own initial attempts at writing ethnography and trying to reduce the mechanisms by which anthropology may describe extreme experiences, I reproduced a different kind of violence of an ungrounded, un-situated account, similar to the intentional suppression present in Majumdar’s work.

Thinking about the relationship between visual art work and ethnography offers a different angle. It's not just that there are many ways to interpret artwork, but more compellingly, there are also none. Instead of, as is done in traditional anthropology, to describe, access, think, and interpret, what would it mean to refrain from such recordings? Such a refrain is one step prior to ethnographic refusal (Simpson 2007) and operates on a different axis: it is not what can or can not be interpreted or described, but what should and should not. How might anthropologists cultivate a disposition of anti-interpretation? What kinds of experiences are not meant to be recorded, documented, described and given any kind of life? As I continued my research and first attempts at writing with this seed in my mind, I already started avoiding asking certain types of questions, attending events, and shying away from the “deep” immersion that is usually expected of anthropologists. What kinds of experiences were my interlocutors going through that should never be excavated?

In Against Interpretation, Susan Sontag (1966) delineates various theories of interpretation of art work. She writes, “by interpretation, I mean here a conscious act of the mind which illustrates a certain code, certain “rules” of interpretation… the task of interpretation is virtually one of translation” (3). Sontag has a somewhat pessimistic view of interpretation. Interpretation, she suggests, is “the revenge of the intellect upon the world. To interpret is to impoverish, to deplete the world, in order to set up a shadow of meanings” (4). Sontag, however, offers another way in which we might interpret an artwork, not by breaking down its elements, not by capacities, knowledge, and intellect of the viewer, but by being against interpretation entirely. “Interpretation, based on the highly dubious theory that a work of art is composed of items of content, violates art. It makes art into an article for use, for arrangement into a mental scheme of categories,” Sontag writes (6). To be against interpretation is to hesitate, to stop, and to allow the experience of art work to wash up on us.

In the world of art consumption, which includes Majumar’s paintings, to resist interpretation is an easier project. One is forced very quickly to confront the potential voyeurism and the appropriation of one’s own gaze in Majumdar’s work. Going against interpretation is permissible with certain modalities, such as paintings, film, and images. With writing, and ethnographic writing in particular, the question of the gaze is further removed because of the detachment inherent to the form(s) of writing and its’ supposed real attachment to the social worlds it is describing. But if anthropology (and theories of madness) is to become decolonized, the task also lies with confronting a colonial disposition of recording, inscribing, interpreting and theorizing life worlds. But what experiences of life should not be theorized? What experiences should stay out of the worlds of academic discourse, up for interpretation, resulting in manipulation at worst and creative associations at best? In other words, what would it mean to not go there, resist interpretation, to be against it? To not document, to not translate, to not describe? Could such a hesitation offer another lens to practices of decolonization?

See Majumdar’s paintings cited in this text.

Bibliography

Clifford, James, and George E Marcus. 1986. Writing Culture : The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography. Berkeley, Calif. ; London: University Of California Press.

Fabian, Johannes. 1983. Time and the Other How Anthropology Makes Its Object. New York Columbia University Press.

Simpson, Audra. 2007. “On Ethnographic Refusal: Indigeneity, ‘Voice’ and Colonial Citizenship.” Junctures, 67–80.

Sontag, Susan. 1966. Against Interpretation.