Interview: Dr Saiba Varma

|

A few weeks after this interview was published, a group of activists, students and researchers raised, through an anonymous Twitter account, ethical and political questions about the ethical responsibilities of Indian researchers in Kashmir, openly critiquing the ethnographic research and writing of Dr Saiba Varma. The group raised important questions about the responsibility of Indian researchers in Kashmir to disclose their involvement in the militarisation and securitisation of the established system of oppression, especially in the context of settler colonialism. As a result, a debate has been opened (or re-opened) within anthropology and other disciplines on the practices of ethics, disclosure and reflexivity when conducting fieldwork, especially in a settler colonial context and within ongoing relations of violence: what are the practices and standards of accountability that researchers should be held to in a settler colonial context? How do ensure transparent and ethical forms of relations? Further statements on the topic by anthropologists of South Asia and a detailed response by Dr Varma can also be found here. The conversation is currently ongoing. |

In this blog, DECOLMAD’s Lamia Moghnieh talks to Dr Saiba Varma, Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of California, San Diego, about her new book, which offers a unique ethnography of medicine and psychiatry in Kashmir by exploring complex interrelationships between politics, violence, medical practices, humanitarianism and mental health. Dr Varma also talks about her impressive research profile and her broader work on foregrounding feminist, antiracist and decolonial practices and methodologies in her discipline.

- How would you describe your scholarship? Tell us about your work, research and your recently published book.

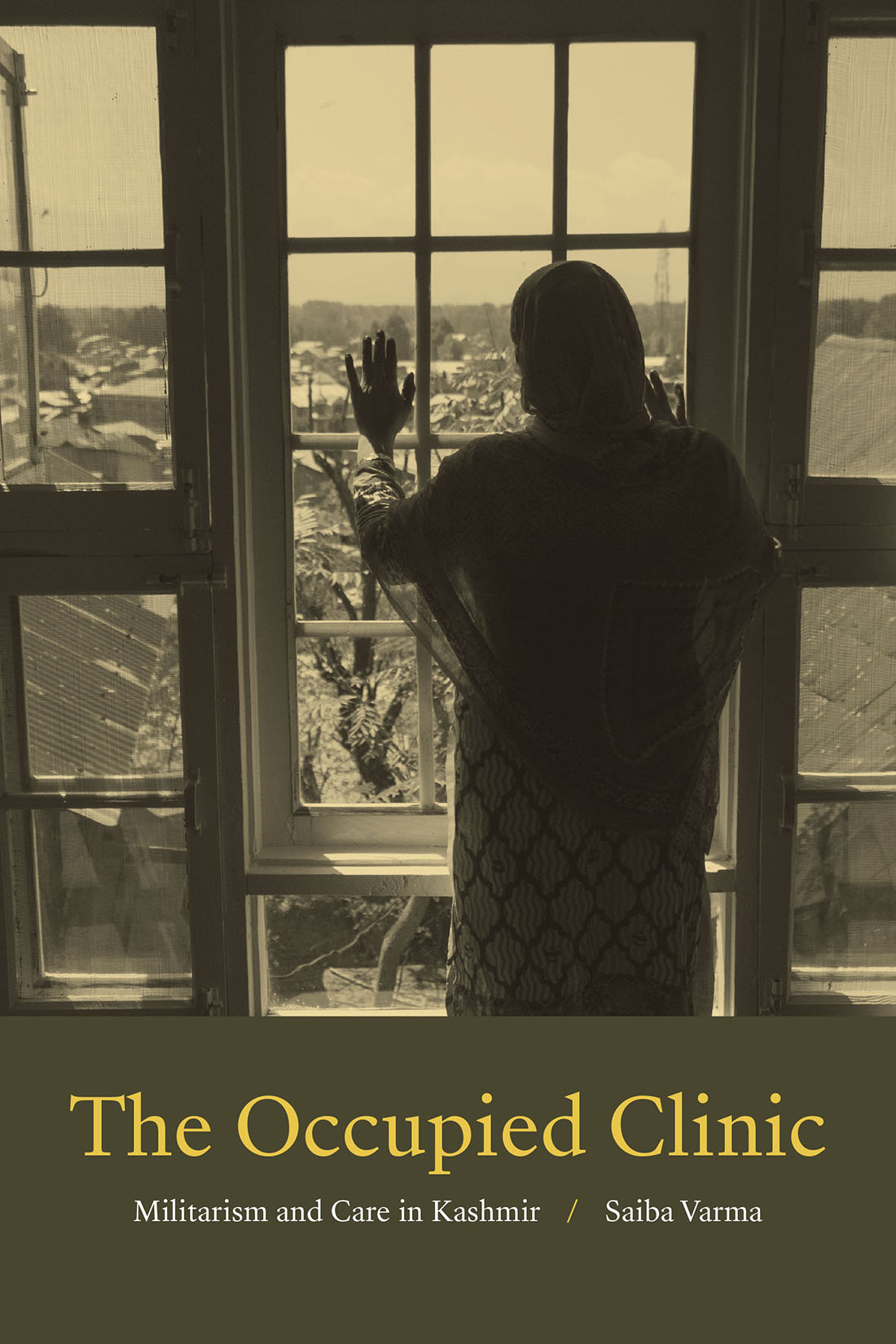

Decolonial, antiracist, and feminist of colour practices and knowledge are central to my work as an anthropologist. My first book, The Occupied Clinic: Militarism and Care in Kashmir (Duke University Press, 2020) is an ethnography of medicine, psychiatry, humanitarianism, and care in a space of occupation. In the book, I ask: how are imperatives to care for a traumatized population reshaped in conditions of long-term violence and occupation? What forms of medicine, ethics, politics, and life are possible in spaces hollowed out by war?

The book is based on more than a decade of sustained ethnographic engagement with psychiatric, humanitarian and military interventions in Indian-controlled Kashmir, the site of the world’s longest-running and most militarized conflict. Histories of occupations, insurgencies, suppressions, and natural disasters have resulted in an “epidemic” of mental illness in Kashmir: more than sixty per cent of the civilian population suffers from depression, anxiety, PTSD, or acute stress. While the Indian state’s colonial occupation of Kashmir (which began in 1948, soon after the Partition of India and Pakistan) has always been justified by idioms of care, love, and protection, in recent years, the occupation has taken on a distinctly medical and therapeutic form, with mental health and humanitarian interventions by the Indian state and military, as well as local and international humanitarian organizations, mushrooming all over the region.

The Occupied Clinic explores the interrelations and overlaps between medicine and militarism. Although medical and humanitarian care is often envisioned as the antidotes to violence and militarism, my work shows how military logic and techniques, on the one hand, and practices and languages of humanitarian care, on the other, interpenetrate and recombine in unpredictable ways, creating disorienting worlds for patients and caregivers alike.

At the same time, the book also documents everyday and collective practices of decolonial care that exist and thrive in Kashmir. Each chapter offers one key example of a decolonial practice of healing and care, whether in the form of cultural production, graffiti, film, poetry, prayer, or forms of hospitality (mehman nawazi) that people draw upon to not merely survive, but thrive in otherwise impossible conditions. In so doing, the book shows how, despite its best efforts, the Indian state does not have a monopoly on “care,” and how practices of care (such as mutual aid, self-reliance, and interdependence) remain critical to imaginations and enactments of decolonial futures.

- DECOLMAD is a project that examines the universality and transcultural application of psychiatry from the aftermath of WWII until the current day, drawing on interdisciplinary accounts on the decolonization of psychiatry and the politics and practices of global mental health. What drew you to study and focus on psychiatry? What are the intellectual and political stakes of studying psychiatry in India, and in what ways was psychiatry entangled with forms of colonialism/occupation and violence in your work?

I became a medical and psychiatric anthropologist very much by accident! When I went to Kashmir on a preliminary fieldwork trip in 2008, I went with only a vague idea of what I wanted to study. I did as anthropologists do – I desperately called and tried to connect with as many people as I could through mutual friends. During that trip, I happened to meet two Kashmiri psychiatrists, who described the mental health crisis that they were facing in Kashmir. They were both very interested in having an anthropologist study this crisis, and I was very compelled by what they described and their willingness to let me shadow them for two years. It was then that I began reading and learning more about the history of trauma, biopsychiatry, PTSD, etc. I didn’t realize it then, but later I felt this was a very important decolonial method, to allow my research to be directed by people on the ground, to study what was important and useful to them.

I think that all academic work has political stakes - but in my case, the stakes felt particularly high. As anthropologists, we should all grapple with the coloniality of our discipline, but for me, this was magnified by the fact that I am an Indian citizen “studying” a place where the Indian state is actively enacting a project of military occupation and violence. I felt deeply implicated. There was no pure position of moral witnessing possible for me.

As an anthropologist of medicine, it was initially easy to ignore some of those complicities or implications because I told me I was studying spaces of care, which were supposedly outside the violence of the state. What I realized in my research was that there are no spaces outside of the epistemological, moral, and political force of colonialism and that medicine and psychiatry bring to light aspects of colonial violence that might otherwise be sidelined or invisible. Here the work of Frantz Fanon was so helpful. In “Medicine and Colonialism,” Fanon talks about how seeing the doctor, the constable, the teacher, and the mayor are for the colonized, essentially the same, that is, the same encounter with a violent colonial apparatus.

In my book, I draw on this but also say that there is something specific about the kinds of harm and violence that are enacted in spaces of medicine. Medicine can normalize, extend, or refract forms of colonial harm in ways that are different from other parts of the colonial apparatus, and there is something particularly violent about turning spaces of care into spaces of harm. For example, people in Kashmir remember how clinics were used as interrogation centres during counterinsurgency operations; clinicians still feel constrained in under-resourced settings that are even more disrupted by regular curfews, strikes, and other suspensions of everyday life and medicine; and living under continuous emergency affects people’s ability to both give and receive care. All of these have lingering, long-term effects. I felt that it was my responsibility to document these more subtle, indirect, and invisibilized effects of colonial violence on people’s bodies, sense of self, and social life, beyond the popular discourses and diagnoses of traumatic stress and PTSD that are on offer. This means, in a way, decolonizing anthropology and psychiatry together, widening our gaze on what we mean by colonial violence and its ongoing effects on people, and creating space for what decolonial healing looks like.

- How do you evaluate the field of the anthropology of psychiatry today? What are some of the emerging debates from anthropological research on psychiatry that you are interested in? What can this field (or subfield) offer?

One of the most interesting and surprising aspects of my fieldwork was that many of the tensions between anthropology and psychiatry – the former being supposedly more attentive to cultural life while the latter is committed to a neurobiological understanding of disease – did not exist. Many, though not all, of the psychiatrists and other mental health workers I met were already practising “cultural psychiatry”. I used to joke with one of my closest interlocutors, a psychiatrist, that he was more of a medical anthropologist than me! He would often talk about the language of distress in the body and tell psychiatric residents that they needed to focus less on the DSM and more on cultivating listening skills. I realized that I did not want to operate from a position of critique, but to think about providers’ complex subjectivities: as people working in a very imperfect system mostly trying their best; and as Kashmiris themselves (many with pro-independence politics) working for the Indian colonial state.

While there is much to rightfully critique about the pharmaceuticalization of the mental health care system in India (and in general the promotion of a biomedical model of mental health care that is rapidly growing in popularity), several brilliant medical anthropologists have already done this. I focused instead on the ways that mental health workers themselves theorized their constraints of working in these extremely challenging conditions. I wanted to think about psychiatry (and clinic) itself as a space of encounter, where miscommunications and mistranslations happen on both sides. While there is now tons of money being pumped into psychiatry and mental healthcare in India, it remains a somewhat marginal and fledgling field; ironically, this means that there is a lot of space for negotiation, compromise, and discussion between patients and providers.

My advice to scholars starting in this field would be to be attentive to the particularities of your field site and see what the dynamics are because knowledge (including anthropological critiques of psychiatry) circulates in very interesting and surprising ways! Often we think we have the critique that is going to pierce through, but in fact, people are thinking about these things already and working with them. I don’t mean to idealize providers--there were many instances where I was deeply frustrated and upset at what I saw. But it was important not to weaponize the intimacy I had developed with them by turning it into cultural critique. I feel that is a very colonial gesture. Instead, I tried to do justice to their complex and often contradictory subjectivities--which we all have living and working in capitalist and colonial structures!

- You are a co-founder of “Patchwork Ethnography”, a working group interested in centring feminist and decolonial methodologies in all phases of the ethnographic process. You co-wrote a manifesto “A Manifesto for Patchwork Ethnography” in June 2020 that was translated into Arabic and Indonesian. This intimately resonates with the working group “ethnography and knowledge in the Arab Region” (of which I am a co-founder and active member) interested in understanding how ethnography can counter dominant regimes of knowledge about Arab countries and in producing a more nuanced ethnographic understanding of the Arab region today. It seems that many anthropologists of /from the global south are creating (out of need) new ways of making ethnography that can account for more ethical and political forms of knowledge production. Can you tell us about the intimate process of founding Patchwork Ethnography, and why are these kinds of creative and critical methodological initiatives crucial for researchers but not accounted for within academic institutions and anthropology departments?

Absolutely! I’m thrilled to learn about your project too, which sounds very much in the same spirit as our patchwork project.

The three of us (Gökçe Günel, Chika Watanabe and I) went to graduate school together and have been friends for almost 15 years. We are also all immigrants to the UK and US who have long sustained relationships across oceans, and for decades, which I think is important to the genesis of this patchwork project. We had been talking informally about our struggles to do fieldwork post-PhD for several different reasons. In the fall of 2019, we decided to think about this more formally and applied for some grant funding which we received. This was all before the pandemic, but certainly, the pandemic crystallized new realities of transnational ethnographic research for all of us.

Our goal with this project was not to coin yet another neologism, but rather to draw together the range of different accommodations, practices, and forms of “less-than-perfect fieldwork” that all of us have been negotiating for a very long time because we do not have the resources for continuous long-term fieldwork, have family commitments that make travel difficult, chronic illnesses or disabilities, caring responsibilities etc. We wanted to centre these stories of disruption to say, simply, that these are not the exceptions, but these are the conditions of ethnography.

For example, as I discuss in my book, my fieldwork has been radically disrupted due to political violence and instability. Nine months into my PhD fieldwork, there were three months of continuous protests, state violence, curfews, and a siege that prevented me from accessing the psychiatric hospital, my main field site. Instead, I spent time sitting in my room, watching Bollywood movies, and reading novels – not doing “fieldwork.” For a long time, I hid that aspect of fieldwork, because I was embarrassed to have “wasted” time. And then, even when I would go into the clinic, I would be unable to access even the most basic “facts” about psychiatry or medicine because people would only tell stories about the gaps or absences of care. I thought these gaps were my ethnographic failures, that I was not gathering the right kind of data. But in writing my book, finally, I confronted these aporias as part of the texture of both ethnography and practices of care in occupation. In doing that, I was able to theorize disruption and political violence as not external, but internal to care. I don’t think I would have arrived at this understanding without embracing patchwork ethnography.

We have been completely overwhelmed by the response we received on our Manifesto and our webinar (which we held this past June)--particularly people’s emotional and affective response, including from women (mothers)/ LGTBQ+ people of colour, precarious faculty, scholars with disabilities, and scholars from the global south -- these were the audiences that we had hoped to reach. We were so thrilled to be able to centre their voices in our webinar. We hope that this will allow anthropologists to be more honest about our “less than perfect” practices and that this honesty will in turn yield new theoretical insights and push our discipline towards a more antiracist, decolonial, just, and compassionate practice.

The Occupied Clinic