Decolonizing Psychology As a Form of Immanent Critique

Lamia Mognieh's interview with critical psychologist Robert Beshara.

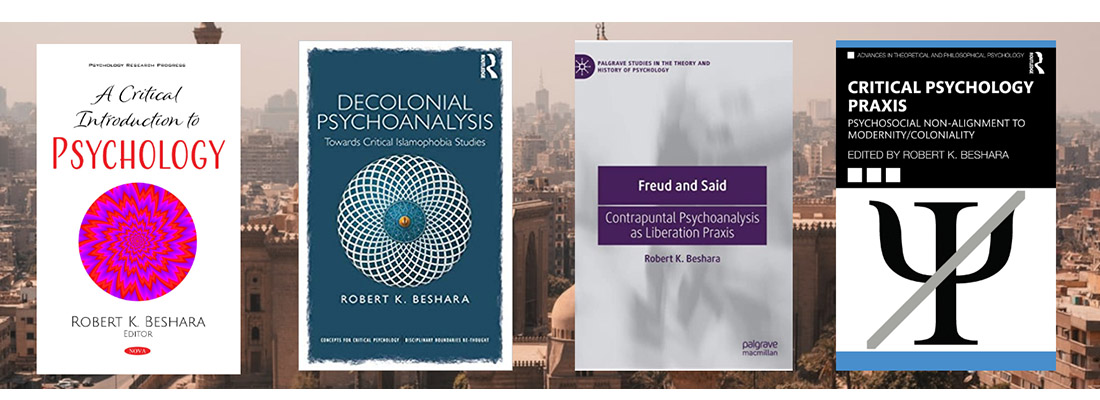

- Please introduce your scholarship and research and talk about your latest publication/ project.

My training is in human scientific psychology, which can mean many things. For me, it means both a theoretical and methodological critique of natural scientific psychology, which is also known as mainstream (Euromodern) psychology and is currently represented by the subfields of cognitive psychology and neuroscience. I will refer to natural scientific psychology as simply Psychology with a capital P since it is a provincial (i.e., Eurocentric) project that claims to be universal.

I gravitate towards critical psychology, which I define as a critical attitude vis-à-vis Psychology, to unsettle the discipline both from within and from without. My critiques from within are often methodological and, hence, index the human scientific tradition of qualitative research, particularly discourse analysis. My critiques from without employ different theoretical approaches, such as psychoanalysis – the repressed other of Psychology according to Erica Burman – and decoloniality. These theoretical approaches among others characterize my commitment to transdisciplinarity.

In addition to acquiring a PhD in Psychology (Consciousness & Society), I hold another terminal degree in film. I say this to underscore my equal interest in, and engagement with, the humanities. For example, my forthcoming publication with Bloomsbury is my translation of Mourad Wahba’s (1995) Fundamentalism and Secularization from Arabic to English. It is an important work of philosophy from the Global South, which is virtually unknown in the Global North as a function of the language barrier. Publishing my translation then signals for me the beginning of a long-term project of translating, and overseeing the translations of, contemporary works by Arab theorists. This is an important move for many reasons, but to highlight one: I want to not only critique Eurocentrism but also contribute in a positive way to a world-centric project. Enrique Dussel qualifies this positive dimension of cultural difference as transmodernity: the best of modernity and its alterity.

- As someone trained in American-style positivist psychology, I am particularly interested in the volume “A critical introduction to Psychology” that you edited, a book that offers a critical alternative to ‘Introduction to Psychology’ Textbooks. What is critical psychology? How can this theory/lens transform the discipline of psychology today (and topics such as self and identity, abnormal psychology and psychopathology, memory and cognition, behaviour, etc)?

Critical psychology, as mentioned earlier, is a critical attitude vis-à-vis Psychology; therefore, it is not a sub-discipline of Psychology. Critical psychology is closely related to the human scientific approach, which was primarily phenomenological, but it draws on numerous theoretical resources beyond that approach, such as Marxism, psychoanalysis, feminism, post-structuralism, and decoloniality. Given that critical psychology is a critical attitude, I see it as a transdisciplinary intervention at the level of praxis. In other words, the aim of its critical theorizing is ultimately social change.

I doubt we can transform the discipline of Psychology, for – as we say about the Democratic Party in the US – it is the graveyard of social movements. Some critical psychologists may indeed want their critiques to be accepted by Psychology, but this path will not result in anything but tokenism. The radical path I am interested in, beyond representational politics, is not concerned with changing the discipline, but with changing the subject to change the world. This echoes the recent turn in critical psychology toward psychosocial studies, particularly in the UK, wherein the psychic and the social are seen as interdependent. By changing the subject, I mean theorizing subjectivity in a complex fashion without reducing it to the brain, cognition, or behaviour. By changing the world, I mean offering practical solutions, through critical theorizing, to social problems. Having said that, I am particularly interested in working with subjects who have been ignored or poorly studied, by Psychology, such as oppressed subjects in the Global North or non-European subjects more generally.

There is excellent literature in critical psychology about all the topics you mention in your question. Instead of reviewing it here, I encourage the reader to search for whatever topic they are interested in along with the signifiers “critical psychology” to see what they find. I also recommend the open-source peer-reviewed journal: The Annual Review of Critical Psychology.

- How did you become interested in decolonizing psychology and psychoanalysis? What does this process mean to you? What frameworks and approaches do you adopt to tackle it? and What are the challenges of doing this kind of work?

I became interested in decolonizing psychology and psychoanalysis for many personal and historical reasons: (1) I am from Egypt, which is not a psychologized society like the United States; consequently, I always have an outsider’s perspective as someone who fares from an Other culture and who speaks an Other language (i.e., Arabic); (2) I started reading Freud as an undergraduate student and was also introduced to humanistic and transpersonal psychologies around the same time, so I was immersed in the critiques of Psychology from very early on; (3) I have been a student of a number of non-European spiritual paths for 20 years, traditions (e.g., Buddhism) that teach their own psychological insights that predate the so-called birth of Psychology by millennia; (4) I was lucky to do my PhD in a Department at one of only two public universities in the US, which honors human scientific psychology; (5) finally, reading texts by postcolonial and decolonial scholars from the Global South (e.g., Said, Dussel, Mignolo, Quijano, Wahba, etc.) as I was researching for my dissertation blew my mind and showed me a whole new way of doing critique that also aligns with where I come from. In sum, as someone from North Africa, who practised in non-European spiritual traditions, and who is an artist first and scholar second, the path that led me to study psychology at the PhD level was far from mainstream. It is worth mentioning, too, that I was into radical politics before learning about critical psychology through the writings of one of its pioneers: my dear comrade Ian Parker.

For me, decolonizing does not mean cancelling. In fact, decolonizing is a form of immanent critique. So, for example, decolonizing psychoanalysis entails critiquing its colonial logic using the language of psychoanalysis to draw out the radical potential of the field, which can sometimes be occluded by historical or cultural contingencies that end up damaging the theory and the practice from within. This damage can clearly be seen in terms of ongoing ethical breaches, whether in the clinic or across psychoanalytic institutions. I try to theorize this damage, not from a Eurocentric perspective, but a Global (Southern) perspective. Therefore, my approach to psychoanalysis is not dismissive, but rather sublating.

To use a concept from Edward Said, I am interested in the worlding of psychoanalysis, which means I want to think about its relevance beyond its inception in Europe for European subjects. For this reason, I encourage the reader, who may be interested in the praxis of decolonizing, to decolonize something they love, which they also think is tainted by coloniality. This does not mean that decolonizing is simply an act of purification, for that is neither an attainable ideal nor a compelling goal. Rather, decolonizing entails delinking to borrow a term from Samir Amin. In other words, the problem with psychoanalysis is not its modern rhetoric about the unconscious, but the colonial logic sustaining this rhetoric, which I theorize as the unconscious of psychoanalysis itself. If left unchecked, this colonial logic then becomes a form of ideological fantasy when the discourse of psychoanalysis ought to be rooted in a concrete material struggle.

My strategy as a researcher is two-fold: first, I use Freudo-Lacanian psychoanalysis to both critique Psychology and theorize oppressed subjectivity, and then I use decoloniality to keep psychoanalysis in check. That is my methodological approach in a few words; however, in my work, I also draw on silenced historical accounts, particularly of racial capitalism as a modern world-system. We are the effects of this history (i.e., hyper-colonization since 1492), and coloniality as a concept signifies the psychic remainder of any form of colonialism. This is why it is relevant to ask questions about the historical conditions for the so-called birth of Psychology in 1879 or the invention of psychoanalysis in 1895. One such condition is New Imperialism (1881 - 1914), or the Scramble for Africa, wherein the majority of the African continent, by the early 20th century, was colonized and controlled by a handful of European powers. This historical condition, and other ones, provided Euromodern psychologists and psychoanalysts with a colonially-embedded theoretical framework about who is ‘civilized’ and who is ‘primitive’ or ‘barbarian’ and why, for example.

The main challenge of doing this kind of work is that it is seen as too political, and therefore as not objective or scientific. This is because it is fundamentally unsettling. However, we must think and act politically and ethically because the historical conditions alluded to above, which framed disciplines like Psychology and psychoanalysis, were also politico-economic conditions, so how can we separate the disciplines’ ideological claims today from the material conditions that gave rise, and continue to give rise, to these ideologies in the first place?

- Thinking about praxis: What are the practical implications of decolonizing psychology and psychoanalysis for researchers, teachers and clinicians? For example, what does it look like to apply a critical qualitative methodology in psychological research? how can scholars, teachers and clinicians practice psychology differently?

Praxis means theorizing as a form of practice, which has effects in the real world (i.e., outside the bubble of academia). The work that we do as researchers, teachers, and clinicians is always situated and contextual, but this work is also informed by the current historical moment, the society we live in, the material conditions of that society, etc. Therefore, we have to seriously ask ourselves: Why are we doing what we are doing? What is the goal here? For me, the goal is liberation (i.e., a society without oppression). If that is the goal, then how do we get there? And how do we prefigure this “there” in the way we do things here and now?