Mending Maladies: Agnes’s Jacket and her kinds

By Subhasree Biswas

My research is about the relationship between women, madness, speech act, needlework and healing. In recent years, the field of Art Brut/Outsider Art is flourishing, which creates new scientific and artistic knowledge. But the female artists of Art Brut are still largely unknown. Women artists and their work in psychiatry were systematically eliminated.

Jean Dubuffet first coined the word ’Art Brut’. He described it as the artwork of the mentally ill, prisoners, children, and primitive artists with the raw expression of a vision or emotions, untrammelled by convention. In the English-speaking world, Art Brut is termed as “Outsider Art” and in Denmark, it is termed as Råkunst.

In recent years, the discourse of Art Brut captured bigger territory than just psychiatric institutions.

It encircles “mediumistic” artists, artists with disabilities, and self-taught artists.

The history of women artists and liberation is tightly knitted, and in the case of Art Brut, it is even more ambiguous. Recently some curators are trying to bring women Art Brut artists to the forefront. Yet ‘writing on textile’ by women Art Brut artists is largely an unknown territory, other than Agnes’s jacket.

On Mend

Mend means something to repair.

The etymology of mend is a shortened form of the old French amends means “a remedy, cure”; It is an obsolete term now. Phrases like on the mend meant the path to recovering from sickness, and they were still found around 1800.

In my research, ’mending maladies’ appears as both metaphoric and pragmatic. On the metaphorical level, the inquiry is broader, questioning how we can mend and heal society, and mother earth.

The capitalist society and its demands for economic growth have put the earth and its people under constant pressure. According to Bernard Stiegler, in contemporary society, Michael Foucault’s notion of biopower is substituted by psychopower: it is the neurons that determine our life.

The achiever society, with more productive and faster mindsets, has left us anxious, depressed and burnt out, creating an innate imbalance in health and society. In a society driven by the motto of ‘survival of the fittest and happiest’, anyone who is unable to perform, achieve, stay normal, positive, and happy is labelled sick, outcasted, institutionalised and medicated; a powerful process of silencing.

Capitalism and its ill effects and practices of care and cure have increased the concerns of artists and activists.

My research tries to find whether art can be a catalyst to mend, repair and restore the damage done to society and the health of the people.

Thus, mending is a metaphor for joining those missing dots between people, the planet, and society seamlessly.

On a pragmatic label, my research is practice-based. I conduct a participatory textile project with recovering mental patients at the Center for Kunst og Mental Sundhed.

For the research practice, the artmaking will take the form of sewing and mending repressed memory, fragmented emotions, and hearing voices. My intention is also to create a vocabulary around madness and maladies; languages, which are otherwise forbidden, express ugly feelings such as traumas, transgressions, and wounds are seen as counter-productive in the so-called ‘Normal’ world. The written words will express struggle, activism, agency and coming into voice from silence.

For the research practice, the artmaking will take the form of sewing and mending repressed memory, fragmented emotions, and hearing voices. My intention is also to create a vocabulary around madness and maladies; languages, which are otherwise forbidden, express ugly feelings such as traumas, transgressions, and wounds are seen as counter-productive in the so-called ‘Normal’ world. The written words will express struggle, activism, agency and coming into voice from silence.

Unlike the usual participatory research, it is not ‘on’ people but ‘with’ people. There is a strong concern over power, participation, and justice and for including all the voices of the participants.

It will invite the participants to take ownership of the sense-making process to create knowledge of their actions.

It is deeply embedded in our culture that only objective knowing is credible, and subjective one is not. Emotions, values, and desires are best kept separated. But in everyday life, we get hunches, intuitions, and gut feelings.

The ‘extended epistemology’ in Action Research embraces these wider ways of knowing that we make use of in our lives and incorporate into our work. As an action researcher myself, I value, we need to know the world in many ways beyond the intellectual.

Background and Inquiries

The late eighteenth century saw a cultural phenomenon that is often discussed as the “feminisation of madness”: the hysterical or melancholic were often women. Women were alienated due to their eccentricities and institutionalised in mental health facilities.

Although alienation and rupture from everyday life caused trauma and agony, for some women these troubled times were also sources of creation. The isolation allowed them a different perspective of the world.

Historically, women patients were allowed to stitch both for productive and non-productive purposes, but it was not considered as ‘art ‘but dismissed as ‘craft’. Due to the lack of medications around the 19th century, sewing and needlework were used to calm the anxious brains of female patients.

My research Mending Maladies: Agnes’s Jacket and her kinds is inspired by Gail A. Hornstein’s phenomenal book Agnes's Jacket: A Psychologist's Search for the Meanings of Madness.

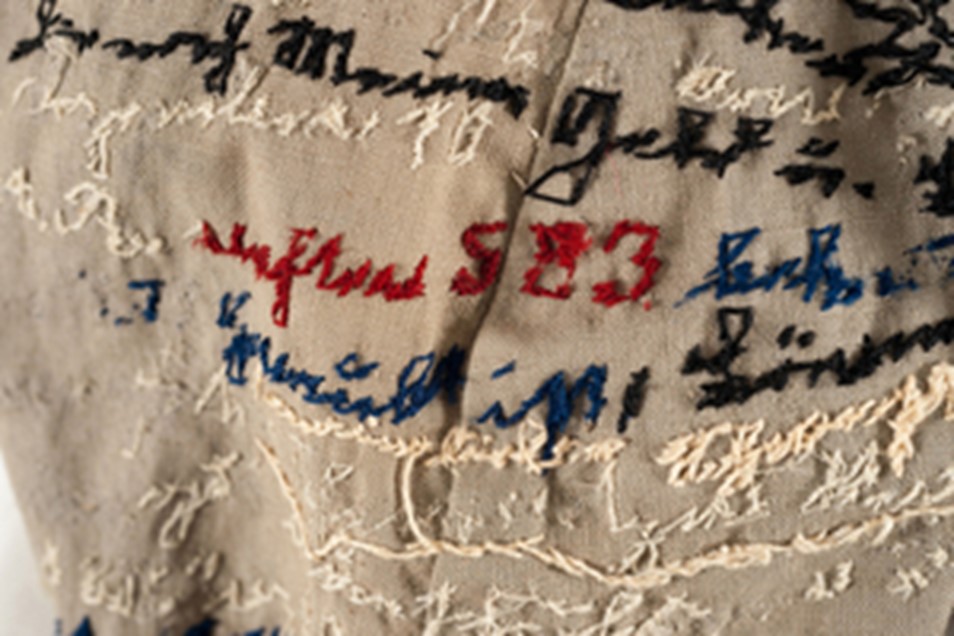

Agnes Richter was a seamstress who was hospitalised in 1895 at the Hubertusberg Psychiatric Institution in Germany for mental illness, where she stayed confined until her death. Agnes used her straitjacket as a diary, where she wrote and embroidered repetitively in cryptic Deutsche Schrift.

Hornstein speculates that Agnes’s jacket may be more of an amulet to ward off evil and usher good luck. She wonders -” Was the jacket a kind of hex, a way for Agnes to turn the tables on her doctors? What if she was like a medicine woman, casting a spell on those who threatened her?”

The jacket was rediscovered in 1980 and displayed at Prinzhorn Collection in Heidelberg. Agnes’s Jacket not only tells her story, but also the stories of her kind, the stories of hearing voices, of people who try to cope with voices, visions, and other altered states of mind.

It was not only Agnes who used institutional linen as her diary, canvas, letters, or as a mode of protest, but around the same time, we witness many women psychiatric patients using embroidery as a mode of communication, to name a few:

- Karoline Ebbesen (1852-1936) in Sct. Hans Hospital in Roskilde, Denmark, made beautiful, embroidered capes with one winged angel and messages written all over. She even made her own script.

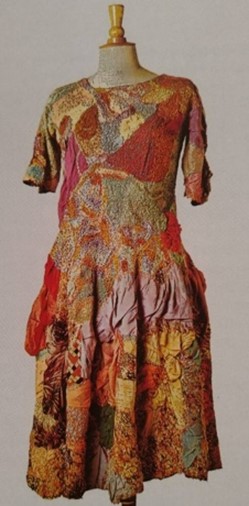

- Madge Gill (1882–1961) was one of the greatest exponents of mediumistic art. We mainly know her drawing and painting, but she was equally skilled in embroidery and often made brightly coloured dresses with elaborate motifs.

- Mary Frances Heaton (1837-1878) from Wakefield, UK made embroidered written pieces, amongst others a letter to Queen Victoria.

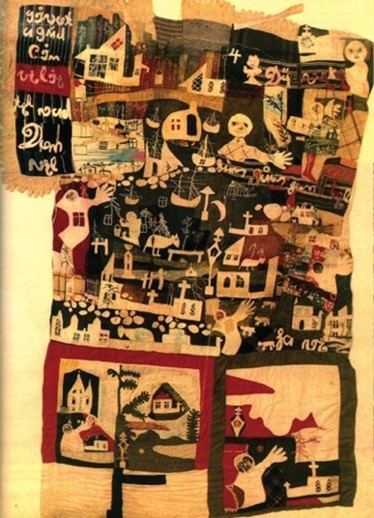

- Marie Lieb (1844-1917) From Southern Germany, was hospitalised at Heidelberg for circular insanity which is now called bipolar disorder. During her hospitalisation, she would tear apart the hospital linen into strips and create installations combining symbols and scripts, which was unique compared to embroidery.

|

|

|

|

We must remember that textile is not mere textile, but also a memory, something close to us or something with which we associate. We can easily imagine that these institutional linens may be the only possession the inmates had which was precious to them.

While my research is inspired by typical archival Art Brut textiles, I am simultaneously interested in investigating the written textile work of contemporary mainstream women artists such as Louise Bourgeois, Tracey Emin, and Annette Messager.

My previous research contains a thread of women, mental health, voice hearing and liberation through writing (Écriture féminine). Women were often stigmatized as witches or hysterics for their knowledge, talent, free will and desires.

In his seminal book, The myth of Mental Illness, Thomas s Szasz established similarities between medieval witchcraft and the contemporary belief in mental illness . In medieval times, witches, saints, and women had hallucinations, had ecstatic erotic moments, fell into trances, had erotic visions, heard voices, fasted, and claimed to have direct contact with God or more than the human world. Women with similar experiences were burned as witches or idolized as saints

and finally medicated as patients, women were stigmatized, and their behaviours were gendered.

In the Middle Ages, witches were made into scapegoats and eliminated from society; mentally ill people have been treated the same way in the modern world.

In recent years, the discourse of Art Brut/Outsider Art captured bigger territories than just psychiatric institutions. It encircles “mediumistic” artists, artists with disabilities, and self-taught artists. As the barrier between ’elite’ art and art brut is diminishing rapidly, the question arises: who are the gatekeepers creating and fetishizing these margins? And how are the boundaries of what is art brut and what is not, decided?

Art Brut is also often an intimate process, not necessarily for public display or recognition. So, further questions arise: what kinds of ethics are followed when displaying outsider art to a wider public?

Who interprets it and how can it be authentically interpreted?

On writing

As the writing of women is an integral part of my research, L'ecriture feminine constitutes a major source of inspiration.

In The Laugh of the Medusa, Helene Cixous explains the subjugation of the female voice by exploring the myth of the Medusa, where she interprets Medusa’s death as men’s attempts to silence the voice of women. Cixous argues that women, by writing their bodies, will no longer remain passive but emerge as a source of power and energy, an identity by itself. Catherine Clément and Cixous mutually focus on the sometimes oppressive, sometimes privileged madness fostered by marginalization, on the wilderness out of which silenced women must finally find ways to cry, shriek, scream, and dance in impassioned dances of desire.

Cixous says that writing is a political act, writing through the body that will sweep away the dominating syntax, grammar, history of reason, the phallocentric tradition, and the burden which suppresses the feminine. The literary text of the libidinal feminine must tolerate freedom from self-limitation and neat borders, from beginnings, middles, and ends, from chapters. It will represent the feminine body as a path towards thought, which will question and deconstruct the foundations of phallocentric discourse, that will break the silencing of women and give women a voice and agency.

It is not only the French feminists who talked about writing with the body. Feminists and scholars of colour also affirm the need for women to write with their whole bodies and unleash the power of erotic, such as Gayatri Spivak and Audre Lorde.

It is worth mentioning that a recent exhibition Écrits d’Art Brut (October 2021-January 2022) at Museum Tinguely, Basel, Switzerland, curated by Lucienne Peiry, focused on Art Brut authors. Most of these writers, including Agnes's Richter, live on the fringes of society, and leave their marks on any surface available, including embroidered cloth and painted walls. These writings contain many emotions: love letters, rage, poems, prayers, erotic messages, pleas, diary-like notes, and utopian narratives. Mostly written behind closed doors, secretly in silence, without address or purpose for another dream world or spiritual addressee. The text written, scribbled feverishly in haste on a paper, embroidered in textile or in carved in wood or stones represents a kind of silent resistance. They are imaginative, uninhibited in their approach and playful in their use of syntax, grammar, and orthography.

Is Art a Guarantee of Sanity?

“The act of sewing is a process of emotional repair”

A recent exhibition called Louise Bourgeois, Freud’s Daughter (The Jewish Museum, New York 2021) explored Bourgeois’s art and writings considering her complex and ambivalent relationship with Freudian psychoanalysis. Bourgeois considered the act of making art a form of psychoanalysis and believed that through it she had direct access to the unconscious. Louis Bourgeois claimed that- “artists have no hope of a cure from a pill, potion or psychotherapy for the anxieties, fears and nightmares which haunt them. Their only recourse is to make art”.

She further claimed art her “guarantee of sanity”.

|

|

|

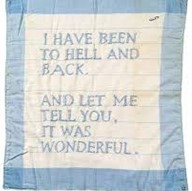

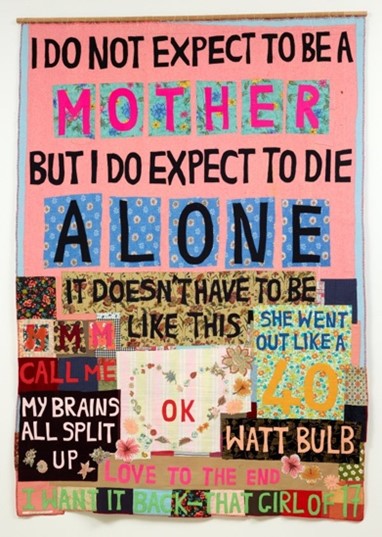

Similarly, many mainstream artists and Art Brut artists embraced Art as a space for sanity such as the written textile work of Tracy Emin, and Annette Messager. All these artists suffered some form of mental illness at a certain point in their lives. Their works are deeply autobiographical, with dark emotions, and nervous energies, and are accepted as mainstream, whereas Agnes’s jacket falls in the category of Art Brut.

Embroidery was once rejected by the art world and considered a craft. There is a gendered hierarchy between art and craft. But many women artists specifically adopted needlework as a feminist form of expression which is traditionally passed on through generations.

Embroidery, mending, applique, patchwork, knitting, and crochet is an art/craft forms mainly associated with women. Recent research says that there are therapeutic benefits of stitching. The repetitive and rhythmic pattern is meditative and calms the anxious brain.

Traditionally women stitched text onto clothes, and fabrics, using thread as ink and fabric as paper. They are often autobiographical, poetic, political, guerrilla, in protest, as confession, as commemoration, and representative of cultural history which is not easy to erase.

My research focuses on the textual and visual practice of the silenced and the repressed. The idea is to make something tangible out of intangible and otherworldly, making the embroidered word a therapeutic or cathartic process.

I am interested to find out the affective role of both therapeutic and subversive stitching and reflect on the relationship between women, maladies, memory (good & bad), speech act, embroidery, and healing. The ugly feelings such as sin, rage, regret, or highly personal emotions such as desire, jealousy, fear, anxiety, and loneliness will be embraced with equal vigour as good emotions such as love, joy, and hope.

Mending will be used as a methodology for care and cure for personal and societal maladies.

Bibliography

Louise Bourgeois Untitled (I Have Been to Hell and Back), 2007. Photograph. Albuquerque: Tate Modern London, 2007. Richard Levy Gallery.

A, Conne. Agnes Emma Richter, Handmade Jacket Embroidered with Autobiographical Text, 1895, Inv. No. 743. Photograph. Heidelberg, n.d. Heidelberg University Hospital.

https://prinzhorn.ukl-hd.de/exhibitions/aktuell/precious-item-of-the-week/jacket/?L=1

Camp, Nathan Van. “From Biopower to Psychopower Bernard Stiegler's Pharmacology of Mnemotechnologies.”

Coleman, Gill. Action Research in Practice: A Beginner's Guide. 1st ed. Routledge, 2017.

Détail Du Travail De Marie Lieb Reconstitué. Photograph. Paris, n.d. LA MAISON ROUGE.

Garde, Karin. “En Vandring i Sct. Hans Hospitals Museum.”

Hornstein, Gail A. “Written on the Body.” Essay. In Agnes's Jacket: A Psychologist's Search for the Meanings of Madness, 353–80. New York, NY: Routledge, 2018.

I Do Not Expect Tracey Emin. Photograph. Australia, 2002. Contemporary galleries.

Madge Gill Dress. Photograph. Lausanne Switzerland, n.d. Collection de l’Art Brut.

Philips. Annette Messager Mes Ouvrages (Possession), 1998. Photograph. NY, 2019.

Sampler Produced by Mary around 1851/52, Addressing Her Concerns to Queen Victoria. Image from the Mental Health Museum. July 5, 2020. Photograph.

Szasz, Thomas Stephen. “Theology, Witchcraft, and Hysteria.” Essay. In The Myth of Mental Illness: Foundations of a Theory of Personal Conduct, 181–98. New York: Harper Perennial, 2010.