Can different providers work together?

Interview with Prof Erminia Colucci

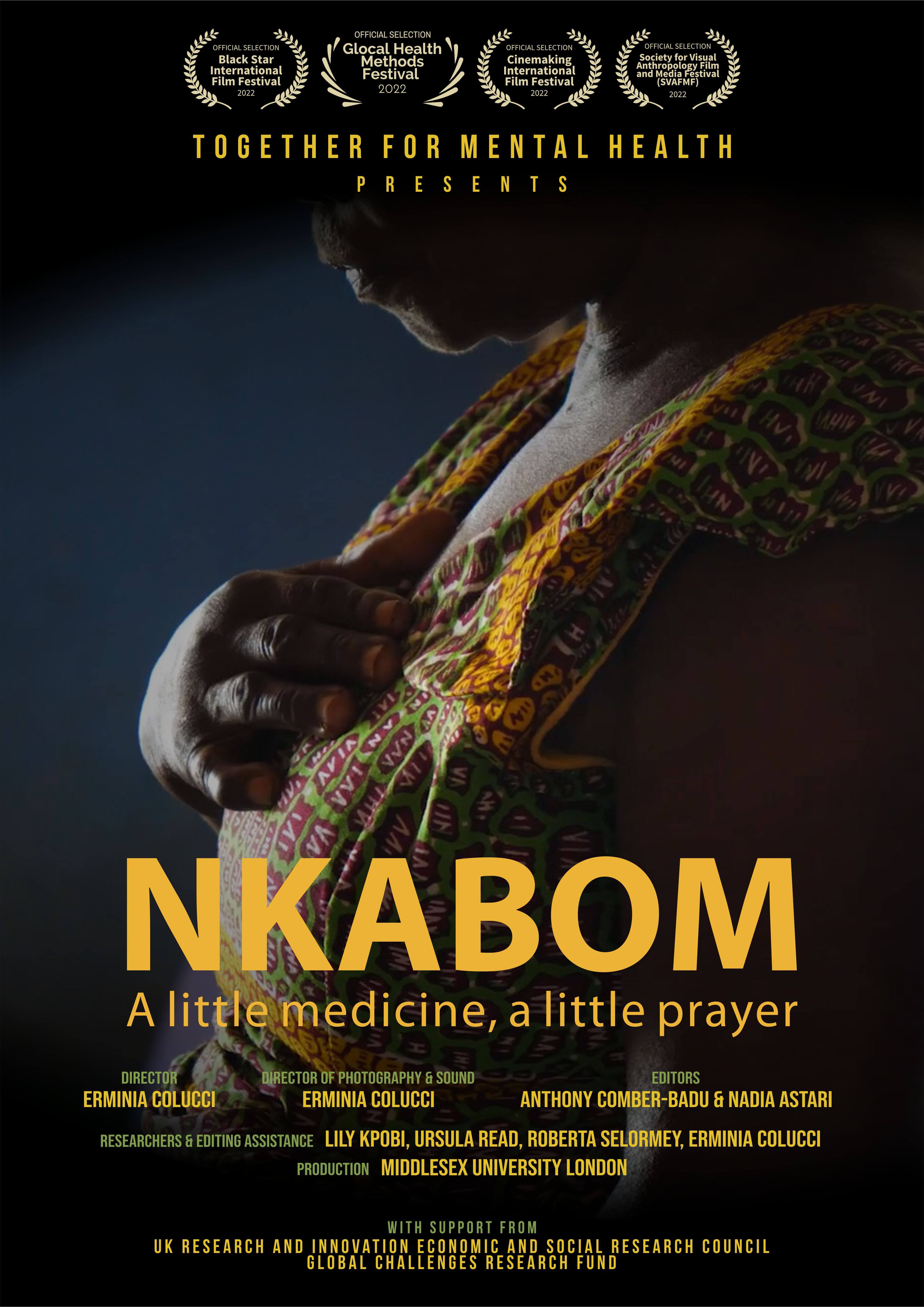

In this blog, I speak with Erminia Colucci, Professor of Visual Psychology and Cultural & Global Mental Health at Middlesex University, London. She is the director of ‘Nkabom: A little medicine, a little prayer’, one of the visual research outputs from the ‘Together for Mental Health’ project which is a Ghana, Indonesia and UK joint initiative exploring collaboration between mental health workers and healers to improve mental health care (see https://movie-ment.org/together4mh). We talked about the motivation behind the Nkabom film, her thoughts about global mental health and collaboration of various mental health care providers/healers and her perception about diagnosis.

|

|

Q.1 Can you please tell as a bit about your reasons for deciding to do this project, choosing Ghana and with your own understanding of global mental health and the kind of mental health service of the Ghanaian community, and how were you able to merge your own beliefs with the local people you engaged with?

In terms of why Ghana, the project came about when myself and Ursula Read, who were at the time at Melbourne University and Kings College respectively, started sharing our own interest with traditional healing and mental health care. Her masters and PhD were in Ghana while mine had been in Indonesia and India.

We started talking about this and our understandings about the similarities and the differences from our observations in these countries and how interesting it would have been to compare some of what we observed in Ghana and Indonesia. That was how the project came about. I did not know anything about Ghana at the time so, when I filmed for this research project it was the first time I went to Ghana. I had a bit of information from Ursula about her work and what she had found, but at the time she had not done any work in Nkoranza. In a way, it was a bit of an exploration for both of us and the local researchers Dr Lily Kpoby and Roberta Selormey about how to carry out visual research in this setting.

What was striking for me was the degree of challenges in community-based mental health intervention in Ghana, which were even more than what I observed during my work in Indonesia. In Ghana, the challenges were more about underfunding of even basic intervention. Despite this, the people working in the field, like George and Liberty in the film, and other young nurses and professionals, showed much commitment because they knew that was the only way they could help others. They committed resources like their own finances to get medications for patients and extra working hours, which was impressive. In addition, there was a very active philanthropist network within the community supporting their work. But the level of commitment of the professionals on the field is not sustainable and that is why almost everybody I met wanted to leave Ghana. A lot of the current UK health workforce are from African countries including Ghana. This shows that the potential and commitment from these young professionals with no resources cannot be sustained and that is sad.

Q.3 How was it for you, as a mental health researcher, coming to terms with the form of mental health care subscribed by the people of Nkoranza you filmed?

Because I have done this kind of research before in India, the Philippines and Indonesia, it was not surprising for me to see that people have a range of mental health care options and choose support based on what makes sense to them and what fits their own beliefs. It is also about what is available, because in all these areas you will find that traditional healers and faith-based healers are present and there is no long waiting list like there is to see a mental health professional for a few minutes. In the big cities like Accra and Kintampo, these services are there at least at some degree, but for most people, (a) this kind of help is not available, (b) when available, it is very far from their communities and (c) sometimes this kind of help is completely unlinked with the people’s system of belief.

It is sad but most mental health services in low-income countries are still fundamentally relying on the use of medications in the same way that it is done in high income countries. The overreliance on medication in low-income countries does not sit very well with most people living in these places because they would not want to do this for the rest of their lives. This is the reality in Ghana and many other countries and so it is not very surprising they access alternative types of care. I found it interesting to observe that the professionals had understanding and tried to integrate the biomedical approach as well as spiritual/religious approach to care. In our case study, we showed situations where the mental health professionals and the healers themselves were able to work together. For instance, the mental health professionals I was working with in Indonesia, accepted that the person would also access help from Imam or traditional healers, and that made it a bit easy for the person with mental illness and the family. The fact that they were able to be in the same space, either in the physical space or in the therapeutic space was rare because for most people these dimensions are completely separated and often conflicting, working against each other. In some cases, the mental health professional will advise not to see the healers and the healers advise against seeing the psychiatrist, and the people are caught in-between.

In my previous ethnographic film “Breaking the chains” (see https://movie-ment.org/breakingthechains), I showed a moment where the uncle of one of the people I was following said: “I go to the psychiatrist and he say don’t go to the healers and I go to the healers and they say don't go to the psychiatrist and I ask what am I supposed to be doing?” The family are hence stuck in this kind of opposing worlds. But the fact is, people are always going to be seeing more than one helper also because the kind of help need are diverse.

Is it possible for the different providers to work together? That was the question our research project tried to address. I think we should raise these structural challenges like the lack of funding we mentioned and the need to encourage a possible collaboration between healers. I think it is the only way because we are never going be able to have enough mental health professionals. Even if we keep training, we will never ever have enough.

Q.4 WHO is advocating for task shifting and sharing approach in various countries...

Yeah, and that is happening but not so much for severe mental illnesses, which is what most people who end up being physically restrained do suffer. The task-sharing approach might be feasible with mild depression, anxiety etc., but with more severe chronic mental illnesses, there is limitation as to what somebody who is not a professional and with no structural support can provide.

Also, in task-sharing /shifting (I prefer sharing to shifting because in shifting, you are giving someone else your responsibility)… so in task sharing, the healers must be a part of it because they are where most people go to, so that sharing needs to be bidirectional. It should be about what we can learn from them as well, because there must be something these healers can also bring into mental health care, even if we might not agree with everything they do.

For instance, I will not say I agree with everything I saw at the healing centres, and there were blatant human rights abuses. Therefore, I am not condoning or accepting everything they do, but there are some aspects of this kind of care which is more community-based and holistic, worthy of learning for application in the biomedical approach of mental health care. We should be open to learn why people continue to see these healers because it might not be just because it is easy to access, available and cheaper, but there might also be something about what a healer of this kind can give to the person which the western (i.e. North-American/European) medical approach is never going be able to give.

There are things about illness meanings and community belief systems, things that are very central to us as human beings, which have been taken out of medicine. Philosophy and religion were once part of medicine, but now medicine and psychology have become ‘areligious’. The downside has been about pushing away these very central human values, which I think people need, and that is why people resort to this kind of possibilities. So how can we integrate a more humane and the human way of providing care?

Q.5 My mind goes to some of these articles that talk about the fact that there isn't much mental health care given in low-income countries, and mostly this is because there is limited biomedical care. But the other forms of care you are talking about, the religious support, etc. are not recognised as mental health care.

It is sad to say, but sometimes this kind of push also has some economic reasons because pharmaceutical companies have a lot to do with this. The labelling, and their associated medicines, do help to make people get better, but there is now an emerging number of studies about things in nature which have similar effects to what pharmaceuticals have. For example, we think about using more naturally produced substances which are good for stabilising mood but can also be controlled (to minimise the risk of abuse), and maybe much cheaper and more sustainable for the environment. All these have been kept under the carpet, without substantial funding to support research and build evidence because there are advantages for pharmaceutical companies and there is financial support for them (e.g. government grants). Pharmaceutical companies also finance certain research, researchers and platforms where to disseminate such research including some conferences. This is why, I ask the question if it is always about caring for people or is it also about somebody making money out of this?

Of course, there are many people who need medication but there are also people who cannot function normally at home and on the job and live a normal life because of the medications they are taking. I am not diminishing the importance of medication, but I think it is problematic that in Ghana, Indonesia, India, etc, the education to the public is that mental illness is a medical issue in their brain, and they must take medication. I think this form of thinking can be very dangerous because it minimises and reduces mental health issues to a purely biological explanation, which can also be, but it might also be something else.

There are also the political, individual and family aspects related to mental issues. All these questions need to be considered and acknowledged. I think that is why sometimes healers are seen to attract more people, because they are providing different perspectives to them. But unless we can also do research to provide the different perspectives and challenge some of these mainstream categories, people in ‘developing countries’ will continue to be highly medicated and never fully recover, which is a great concern.

Q.7 Thinking of the decolonization of mental illness and transcultural psychiatry, there has been concern about assessment tools and diagnostic criteria. Could you please share with me your thoughts about the universality of these criteria?

As a psychologist, I think that diagnosis as a form of communication has a place in mental health as long as we see them as a tool for communicating between professionals. For instance, when we say “major depression”, there is a common understanding of what to expect in terms of symptoms. They are simply a description of symptoms, so if you are using them as a description of symptoms we can communicate with each other, they have a place in the mental health discipline but making it an ontology becomes a problem.

For instance, an illness called depression has some specific features in the USA, but in Ghana we might not so good in assessing it. As a result, we continue doing research to develop assessment tools that will give us ‘depression’ as we think of it is in the USA or UK. This is an imperialistic approach and that is what people, like myself, are questioning.

A lot of mental health training for professionals like myself as a psychologist was about being able to diagnose and this was the first stage for therapy. Hence, diagnoses play a role but they should not be the central point of what mental health care is about.

We need to restructure the training of mental health professionals to bring them the understanding that diagnostic categories come from North America or Northern Europe and are located in a specific cultural background, class and gender, and their applicability is limited in other contexts even in the North America and in North Europe. They should hence be used only as descriptive tools with their limitations.

For instance, conditions may present differently, but more than just the presentation, what we call depression might be something completely different in another cultural context, perhaps it does not even exist in that context. Again, are depression and suicide ultimately the same thing everywhere or could suicide be about the sense of meaninglessness and?

So it is about really questioning the ontological nature of these concepts because some of the behaviours or situations may be something completely different in different cultures. Focusing on presentation of symptoms is thinking they are the same thing, they just look different in different contexts. But it is possible they are not at all the same and it might not even exist. In this sense, it would be counterproductive to try to make them the same treatments and propose the same solutions. There is a very interesting work from Andrew Rider in Montreal who has been looking specifically at diagnosis and I strongly recommend it.

Q.6 I would want us to talk about your Covid-19 video-based participatory research with people living with psychosocial disabilities. Your participants used various ways (including artwork) to communicate their Covid-19 experiences and the impact on their lives. Could you tell me what kind of change you were hoping to bring them from using this method of research?

The lead of that project is Ursula Read and she is leading the papers about this project which we are looking at disseminating soon. But what I say is, being on the field, what has been interesting is the impact this kind of methodology has directly on the people and their caregivers. It made them feel that we believed in their ability because most people think if somebody has severe mental illness and have low educational level, they don’t have much use, let alone, make a film. So, for us to completely trust what they could do and to supported them to create a story, choose how the story should be told was a new experience for them, I feel it gave them agency, that agency that is usually taken away from them. For me, the impact this project had on the people themselves and the community around is the most significant particularly, giving them a sense of confidence and a belief in themselves. Self-advocacy is crucial in mental health care and activism, as shown in https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jGALhkwzg4g&t=1432s