Newsletter 15 September

Dear Reader,

Hi, I'm Christina Fogarasi, a literary scholar focused primarily on contemporary American fiction, with an emphasis on representations of trauma and disability. Critics of contemporary "trauma fiction" (including myself) often worry that the genre explains everything about a character through her past trauma, such that "trauma has become synonymous with backstory," operating as a key that unlocks the character's truth.

In light of this cultural investment and subsequent critical reactions, I've become curious about how antecedents to trauma fiction - fiction interested in ‘madness' and psychological suffering more broadly - situates character backstory. What place does a character's history have in the story itself as well as in the critical conversation? And how does that history emerge without the intrusive flashback that dominates the contemporary trauma aesthetic? In short, what does backstory look like before the rise of PTSD?

Heading into this semester teaching 20/21 C American Gothic Fiction, I've become fascinated by a canonical cohort of disturbed and sometimes "hysterical" Gothic women protagonists with shockingly boring backstories. The main characters in Charlotte Perkins Gilman's The Yellow Wallpaper (1892), Henry James' The Turn of the Screw (1898), and Shirley Jackson's The Haunting of Hill House (1959) are all relatively sheltered or confined young women, saddled with burdensome domestic duties. Their various symptoms derive, according to critical consensus, from sexual repression and patriarchal control.

At the moment, I'm less interested in treating these characters as case studies or stories as political commentaries (there's plenty of good work out there!), and more interested in how these socio-political concerns - cultural anxiety around gendered freedom - re-directs narrative energy. Instead of moving towards the past through a series of revelations, the stories sideline the past, such that the protagonists' disturbing collapse of external reality and internal world becomes the focus. The stories turn away from obsessively unraveling a character's history (even as certain readings may nonetheless insist on unearthing this) and move towards immersing readers in the imaginative, fantastical, and - some might say - delusional worlds the women create for themselves in the present.

Through these examples, we're taken to a strikingly different moment in literary history, when backstory is implicitly mundane and perhaps even impersonal (at least according to the narratives themselves). The texts re-conceptualize literary character and, further, re-think what we should care about when we encounter psychological suffering, as formative experiences are discarded in favor of aesthetic immersion in psyche. Like lead characters from British romantic period (1798-1837), the women here become ‘worthy' of protagonist status because of their extraordinary capacity for feeling.

What strikes me repeatedly is the open-endedness of the protagonists' fantasies. All three texts leave open the possibility that the ‘delusions' exist beyond the protagonists' minds – that they are ‘real.' Further, all three texts suggest these experiences may indeed be pathological. But there is plenty of evidence to suggest that they may also, in fact, be subversive, offering access to a feminist solidarity or taboo pleasure. Perhaps they are both.

Ultimately, the texts' aesthetic and narrative ambiguities force us to dwell in an uncertainty that usefully slows down the interpretive process, inhibiting the (often anachronistic) impulses to diagnose and instrumentalize. The ambiguities push me and my students to think outside the now-dominant logic and language of PTSD, not so much to suggest other diagnoses but rather to contemplate the alternative philosophies of self, of political commentary, and of art these texts put forth.

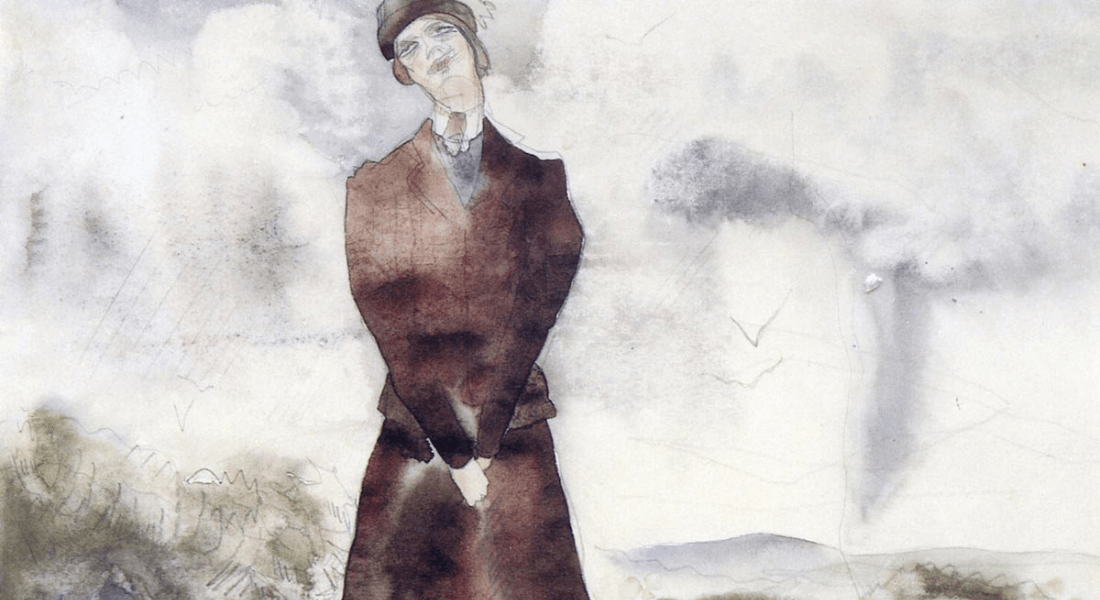

"The Governess First Sees the Ghost of Peter Quint" by Charles Demuth (1918)

A painting of the protagonist of Henry James' The Turn of the Screw

Subscribe to our newsletter

Enter your email to subscribe to CULTMIND Kaleidoscope.