Newsletter 4 April

Dear Reader,

The calls to reimagine psychiatry feel increasingly difficult in today’s harsh global and sociopolitical context. We witness how mainstream psychiatry often fails to engage with core debates on (neo)colonialism and genocide, the concentration of capital, and the forms of exploitation that have led to the destruction of communities and nature and the resulting climate crisis, among other issues. At the same time, psychiatrists—and mental health professionals—overwhelmed by the privatization of services, budget cuts, and high demand, tend to reduce social malaise and suffering to diagnostic categories; limit the understanding of "the social" to "social determinants" and "risk/protective factors"; and approach politics merely as the need for better health and social policies. Meanwhile, we see how multiple forms of affliction and individual and collective suffering proliferate globally, especially among the most vulnerable.

Even so, precisely because of this, we must reimagine psychiatry today more than ever. Inevitably, reimagine psychiatry necessarily implies a return to the history of psychiatric practices, as well as making intelligible those practices that, over time, were relegated to the realm of the "impossible." However, with this, I am not calling for a "going back" in history or a certain romanticization of past experiences such as those carried out by now-recognized figures like Tosquelle, Fanon, and Basaglia, among others. Instead, a historical approach to these practices would involve identifying, for example, those global mechanisms that, since the second half of the twentieth century, gradually led psychiatric institutions and mental health professionals to disengage from discussions about geopolitics and its impact on people's daily lives, the depoliticization of their practices, and even those practices that led professionals to be considered "enemies" by groups of (ex)users and survivors of psychiatric treatments in various latitudes.

My current work seeks to interrogate the relationship between psychiatry and utopia. I explore how health institutions, psychiatry, and psy-professionals have engaged, to different extents, with ideals of social transformation and well-being. To do so, I draw on Chile's recent history. The country is relevant for global discussions in this matter for two reasons. First, Chile became a political and intellectual niche that sparked diverse radical experiences in psychiatry during the progressive governments of Eduardo Frei Montalva (1964–1970) and Salvador Allende (1970–1973). Second, the role played by the USA and the CIA in the destabilization of the country, the 1973 coup, the subsequent political violence and repression during the civil-military dictatorship (1973–1990), and the implementation of the so-called "neoliberal experiment" provided the foundations for the elimination of those experiences, the privatization of the health system, and the psychiatrization of (social) suffering. Thus, the country becomes an excellent case study for exploring the relationships between politics, ideologies, psychiatry, and utopian ideals.

Not only archival and ethnographic research has informed my work in recent years, but also many other sources. For example, the documentary trilogy "La Batalla de Chile: La Lucha de un Pueblo Sin Armas" (The Battle of Chile: The Struggle of an Unarmed People) (1975–1979) and the documentary "Nostalgia de la luz" (Nostalgia for the Light) (2010), both by Patricio Guzmán, allow us to reflect on geopolitical issues, repression, and the effects on everyday life in Chile. Similarly, the books "Formas de Volver a Casa" by Alejandro Zambra, published in 2011, and "Space Invaders" by Nona Fernández, published in 2013, allow us to consider the intersections between political violence, neoliberalism, and the promises made to a generation of children and adolescents who became adults during the post-dictatorship.

By Gabriel Abarca-Brown

Postdoctoral Researcher

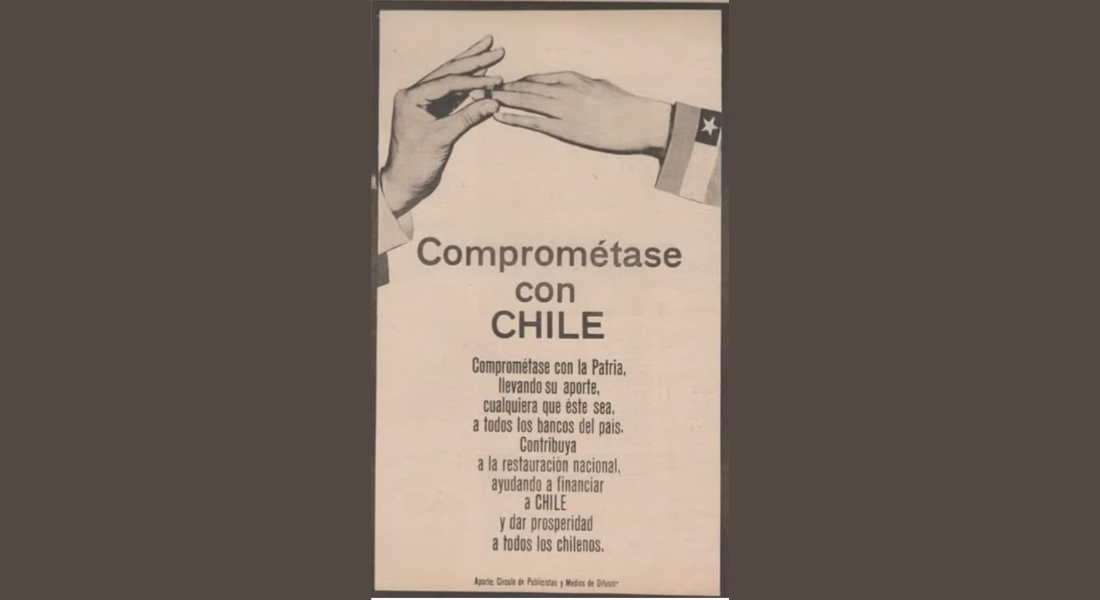

La Tercera Newspaper, October 9, 1973 - The "Commit to Chile" campaign was carried out by the civic-militarydictatorship to "restore" the country after the military coup.

La Tercera Newspaper, October 9, 1973 - The "Commit to Chile" campaign was carried out by the civic-militarydictatorship to "restore" the country after the military coup.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Enter your email to subscribe to CULTMIND Kaleidoscope.