Seeking parallels in the new trends and paradigms in contemporary arts and social research in (Global) Mental Health

by Felipe Szabzon

This summer I visited two great exhibitions: The “Documenta Fifteenth” in Kassel, Germany, and the “Forensic Architecture – Witnesses” in Louisiana, Denmark. Both exhibitions called my attention to an emergent paradigm that has been challenging artists as well as social scientists in today’s world – the need to bring a diversity of experiences and perspectives from different contexts around the globe to the fore, focusing on collective and unadorned accounts of common people instead of refined and sophisticated perspectives of renowned personalities. Although very different in their ambitions, formats and nature of the works presented, a similar idea underlies their curatorial proposal provoking structures of power and oppression and, at the same time, giving space to new voices, testimonies and perspectives that are frequently silenced and repressed.

This text inaugurates the blog section of the project “COVID-19 and Global Mental Health: The importance of Cultural Contexts”. In it, I will comment on my impressions about potential parallels that could be established on new trends and paradigms in the art scene as well as in social research. As a social researcher myself, I am concerned with understanding the relationship between politics, policies and social structures and subjective experiences of marginalised groups. Over the previous years, I have been investigating different kinds of suffering and moral conflicts that affect vulnerabilised communities in different contexts around the globe. Often, these experiences of suffering are simplistically framed as mental health problems or individual psychological issues. The main problem with this simplification is its disregard for the context in which these experiences are forged, shaped and lived. The two exhibitions that I will comment on in the following lines shed light precisely on this issue, giving an aesthetic body to different forms of seeing the world or creating new narratives of everyday life. If processes of vulnerabilisation can silence so many voices, arts, technologies and new paradigms of science have been trying to break this pattern by exploring new tools and methods to shift this trend.

The Documenta is an exhibition that takes place every five years. Created in 1955, the exhibition endeavoured to bring Germany back into dialogue with the rest of the world after the end of World War II, and to connect the international art scene through a “presentation of twentieth century art.” In its first edition, Documenta presented art that the Nazis had deemed degenerate, with works from major movements (such as Fauvism, Expressionism, Cubism, the Blaue Reiter, Futurism) and individualists such as Pablo Picasso, Max Ernst, Hans Arp, Henri Matisse, Wassily Kandinsky, and Henry Moore. Since then, Documenta have been arguably the world’s largest exhibition of contemporary art and an important reference on the avant-garde.

In its fifteenth edition (on show from June 18th until September 25th, 2022), the Documenta Commision has appointed Ruangrupa as this year’s artistic director. Ruangrupa is a collective founded in 2000 and based in Jakarta, Indonesia. As a non-profit organization, Ruangrupa promotes artistic ideas within urban and cultural contexts through the involvement of artists and other disciplines such as the social sciences, politics, technology or the media so as to open up critical reflections and perspectives on contemporary urban problems in Indonesia. The commission justified its decision for choosing Ruangrupa, among other things, with the collective’s participatory approach: “At a time when innovative power emanates in particular from independent, collaborative organizations, it seems logical to offer this collective approach a platform in the form of documenta.”

The Louisiana, on the other hand, is a modern art museum with permanent as well as temporary exhibitions. Founded in 1958, it was intended for the museum to be a home for modern Danish art. After only a few years of existence, the museum changed course, and instead of being a predominantly national collection, it became an international institution with many renowned works from artists from several countries. Up to date, Louisiana is among one the leading modern art institutions of Europe and beyond.

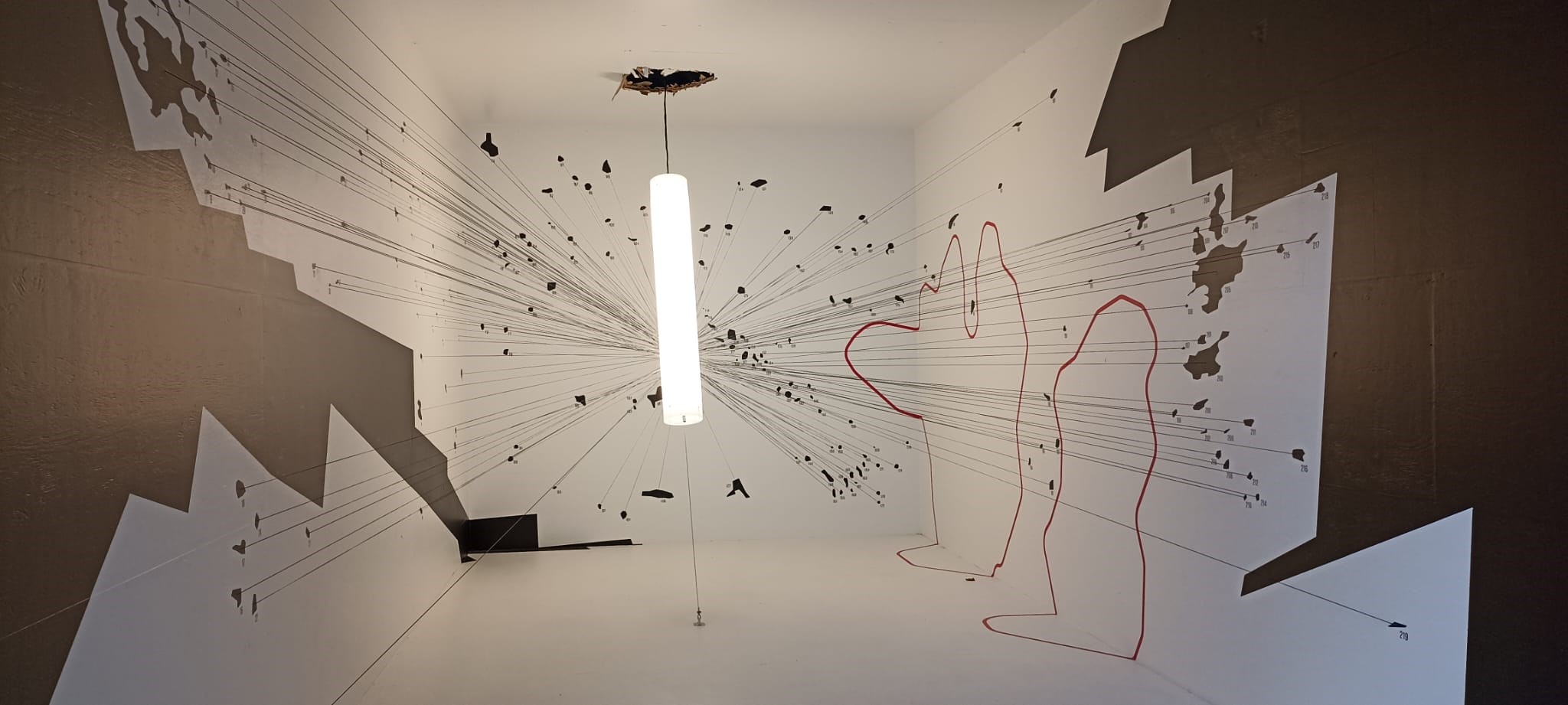

Amid other projects of the museum, the Lousiana is hosting a series of exhibitions entitled “The Architect Studio” which examines the design process and working environment of contemporary architects. The fifth show of this series presents Forensic Architecture (on show between May 05th and October 23th, 2022). The Forensic Architecture (FA) is an interdisciplinary research agency, based at the University of London. Working at the intersection of architecture, law, journalism, human rights and the environment, Forensic Architecture investigates conflicts and crimes around the world. The research agency is dedicated to “solving crimes against civilians, in part by analysing architecture and landscapes based on the idea, and the awareness, that not only people but all matter has a memory, and that all memory is bound up with spatial perception”. The agency uses architectural practices and methods to uncover and gather evidence and testimonies about state crimes, often bringing witnesses' perspectives to the centre of the investigation. This practice goes on the counterhand of official narratives in which the information provided by witnesses is often discredited or placed in question, due to the “distorted memories” caused by traumatic circumstances in which these events occur.

Both exhibitions can be seen as important references about the most recent debates in the contemporary art scene. Interestingly, rather than relying on exhibitions of prominent artists with renowned trajectories, what is on stage are the voices of commonly unheard people, generally from deprived communities presenting their work, versions of history and worldviews. Also remarkable is the fact that in both cases, exhibitions are a product of collective work. Behind the name of the collectives, the individuals that compose these groups barely get any prominence.

In Documenta, I could learn about the struggles of people from all over the globe. Take for example the work of the Archives des luttes des femmes en Algérie. Through several interviews and a selection of archival documents, I became acquainted with Algeria’s largest popular uprisings that took place in 2019, known as the Hirak where millions took to the streets to protest against the government. The work highlights the connections between present and past political struggles proposing a fragmented chronology of women’s movements and mobilizations in Algeria. Or the work of Keleketla!, from South Africa, which highlights the problematics of depoliticization of cultural work, and demands the government’s accountability for the neglect of cultural infrastructure in Johannesburg. At documenta fifteenth, they showcase a work in which they invited local stakeholders to diagnose and pinpoint communal solutions to civic problems. Another beautiful work was authored by Komîna Fîlm a Rojava, a collective of filmmakers from northern Syria that offered to visitors selected pieces of the commune’s archival and recent films, as well as examples from Kurdish film history. They show the violent politics of forced assimilation of Indigenous communities leading to an erasure of their specific histories and artefacts. As they recall, the war in Syria magnified these problems and brought further challenges as the Rojava region suffered attacks and occupation from Daesh.

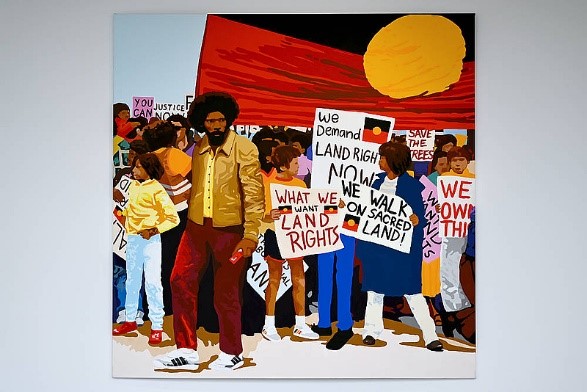

I must also highlight the work of OFF-Biennale Budapest that showcases the (im)possibilities of a “RomaMoMA” (Roma Museum of Contemporary Art), given the exclusionary tradition of Roma artists. The work of Richard Bell, who grew out of a generation of Aboriginal activists from Australia that, so clearly, explores the complex artistic and political problems of Western, colonial, and Indigenous art production in the country. The poetic movies of Saodat Ismailova , from Tashkent, Central Asia, that revolves around the figure of the chilltan, and in which she mingles her own image in dream-like scenes that take the form of young or elderly women and animals, such as snakes, birds, or tigers, animate or inanimate parts of nature, and even natural phenomena like wind or clouds. Or even the performance of Trampoline House, formed in 2010 by a group of artists, curators, refugee rights advocates, and asylum seekers as an antidote to Denmark’s asylum, refugee, and immigration policies. And these are just a few of the artists presenting at Documenta Fifteenth.

The exhibition as a whole is at the same time sensitive and beautiful, displaying the multiplicity of possibilities of cultural life on earth, and a punch in the stomach as it highlights the injustices of today’s world and the suffering it generates.

In the case of Forensic Architecture, I could also learn about the histories of communities and places, affected by state and corporate violence. Although much smaller in scale, the exhibition showcases different projects of the agency. In one investigation FA make use of “situated testimonies” of local peasants to map the mechanisms of land dispossession in Nueva Colonia, Colombia. This process has led to the dispossession of campesinos, and the transfer of their land to companies for commercial mono-crop banana cultivation. The project shows how dispossession occurred in the shadow of armed repression, massacres, and terror spread by private paramilitary forces, serving local and international banana producers under the protection of the Colombian military. The show also exposes how these producers benefited from the dispossession of campesinos and how the changes in the landscape were used to erase memory, avoiding future restitution of land, and traditional forms of social organization and farming. The exhibition also features a montage in which forensic architects reconstitute a drone strike in Miranshah, Pakistan. The work of Forensic Architecture has allowed challenging the official US governmental narratives about the use of missiles in civil neighbourhoods, in an action that killed hundreds of people during the war on terror in 2012. The exhibition also showcases the reconstitution of the scene of the execution of Ahmad Erekat, a 26-year-old Palestinian, who was shot by Israeli occupation forces after his car crashed into a booth at the ‘Container’ checkpoint between Jerusalem and Bethlehem in the occupied West Bank.

In both exhibitions, the use of technologies and the public recognition of the curators were particularly important to give voice and legitimacy to experiences lived by common people that took place in a very specific time and place. What is at stake in virtually all pieces of art is not the geniality of a given artist, but the increasing need to shift positions of power and learn with those in worse-off situations. Every single artwork is carefully displayed in a way that visitors can always situate them in particular contexts and put themselves in the moral position of the artists or victims, understanding their struggles and anguishes. Testimonies in first-person are the rule of law in virtually every work, moving away from traditional paradigms in which artists used to interpret and analyse their surrounding world, to another form of bringing the “reality” into the museum in which visitors can learn, reflect and react directly to the experiences of common people living in the frontline of conflict.

And what can these exhibitions tell us about contemporary research on (Global) Mental Health?

Similarly to the current trends in the contemporary art world, there is a growing scholarship using new methods and participatory practices to bring the voices of mental health service users or communities in psychological suffering to the fore. These new scholars call attention to the multiple social, cultural, political and economic spheres in which suffering is produced around the globe.

Over the previous years, I and a team of researchers from Brazil have been collecting testimonies about the psychological distresses posed by COVID-19 to people living in the peripheries of the city of São Paulo. Other than reporting fear of death and contamination by the virus or the challenges of staying home for such a long time, people often referred to the psychological malaise that unfolded from neoliberal policies and the escalation of insecurities (such as food, income, violence, or education) during the times of the pandemic (Abarca Brown et al., 2022; Bruhn et al., 2022).

Similarly, our current research project at the University of Copenhagen, “COVID-19 and Global Mental Health: the importance of Cultural Context”, is in close dialogue with a similar perspective proposed by the exhibitions of Louisiana and Documenta Fifteenth. In the following 20 months, we will be collecting reports and evidence about lived experiences in different regions of the world, exploring how context and culture are so important for understanding the nature of the mental distresses generated by the pandemic worldwide.

Both exhibitions directly intervene in traditional debates about the processes of inclusion/exclusion of people with lived experiences with mental disorders and surviving traumatic experiences. The work of Project Art Collective, for example, presented at Documenta, produces and disseminates art underpinned by radical approaches to neurodiversity, rights, and representation. They coin the term neurodiversity, composed of neurology and diversity, to refer to a growing movement for broader acceptance of the multiple possibilities of perceptual processes, behavioural patterns, and forms of representation. Or in the case of bringing the voices of “traumatic memories” of victims, as proposed by Forensic architecture in the Louisiana.

Nonetheless, the lessons brought by the exhibitions to (Global) Mental Health research should not stop here. In both cases, the curatorial proposal goes much further than promoting the inclusion of people with mental disorders and helps us recall to the importance of resorting to context and culture when debating mental health in a much broader form in different settings across the globe. Both exhibitions resort to an understanding of (Global) Mental Health that is necessarily political, contextual and moral. They recall to the importance of revitalizing values such as social justice, rights, inclusion and equality to address contemporary suffering.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, many have raised the flag of a new tsunami of mental health problems that should take place worldwide (during and after the pandemic). Indeed, what we have seen so far is that people are suffering practically everywhere. In its most wild and simplistic reading, this problem has been addressed especially with psychotropic drugs and individual psychological treatments[1]. Nonetheless, far less importance has been attributed to understanding the structural problems that lay beneath these sufferings and distress. The testimonies presented in both exhibitions speak for themselves about the current situation in which we live.

As in so many crucial times of our history, art has played a decisive role in helping us to better understand the realities we are embedded in and to move forward by forging new trends and paradigms. We hope science can do the same and stand in a similar position at the forefront of this contemporary shift that is underway in the art scene.

References and Links

Bruhn L, Szabzon F, Abarca Brown C, Ravelli Cabrini D, Miranda E, Andrade LH. Suspension of social welfare services and mental health outcomes for women during the COVID-19 pandemic in a peripheral neighborhood in São Paulo, Brazil. Front Psychiatry. 2022;

Abarca Brown C, Szabzon F, Bruhn L, Ravelli Cabrini D, Miranda E, Gnoatto J, et al. (Re) thinking urban mental health from the periphery of São Paulo in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int Rev Psychiatry [Internet]. 2022;0(0):1–11. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2022.2027349

Forensic Architecture - Louisiana Museum of Modern Art

Investigations ← Forensic Architecture (forensic-architecture.org)

documenta fifteen (documenta-fifteen.de)

[1] For example see: The Age of Distracti-pression - The New York Times (nytimes.com)